Vijender Singh will fight Kerry Hope on July 16 in New Delhi.

Vijender Singh will fight Kerry Hope on July 16 in New Delhi.

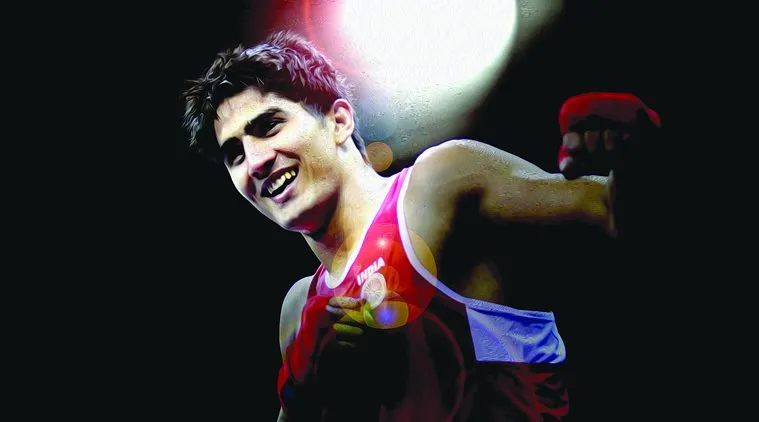

Vijender Singh’s homecoming in his first pro bout at Delhi’s Thyagaraj Sports Complex will be a good indicator of how ready India is to welcome the boxer and boxing in their new avatars, says Jonathan Selvaraj

Built during the heady construction boom ahead of the 2010 Commonwealth Games for the purpose of hosting the netball event, Thyagaraj Sports Complex, in central Delhi’s neighbourhood of INA colony, has gotten used to a more low profile role post the Games. It’s hosted the odd Pro Kabaddi League game and a few corporate tournaments but for most part Thyagaraj sports complex, despite its imposing concrete and glass structure, stays in character with its decidedly middle class surroundings. Outside the stadium, kids sprint on the synthetic running track. Other teens kick a football in the grassy space bounded by the track. Some parents keep watch from the concrete steps built into the side of the stadium while others simply snooze.

But Thyagaraj will break out of character this weekend. The venue, named after the medieval Tamil Carnatic composer, will witness heart-throb crooner Guru Randhawa belt out Punjabi love songs even as Bollywood actors, cricketers, politicians take their seats at the indoor venue. The wooden netball floor would have been covered up to fit in more seats, some 5000 in all, until just enough square footage remains to hold the squared circle.

Inside that canvas, former Olympic medallist Vijender Singh, still undisputedly the biggest name in Indian boxing, will do battle over 10 rounds with veteran Australian Kerry Hope. Vijender will be hoping the fight ends with him holding up his first professional title – a WBO Asia Pacific super middleweight title belt.

If you take Vijender’s promoters at their word, Thyagaraj will likely have seen nothing like it and certainly not Indian boxing. “This will be the biggest sporting event featuring an Indian in July,” says Neerav Tomar, MD of IOS which manages the Indian.

Interest in the amateur format spikes over intervals of four years, whenever the country’s pugilists box in one of the continental games or tournaments. But at least the boxers have a structure to speak of. For the most part, professional boxing has never really picked up. There have been a few bouts organised sporadically – a WBC Asia Pacific title fight last year, and AIBA’s own APB organised a bout featuring World medallist Vikas Krishan a few weeks back.

But both of those bouts were ineptly managed affairs. They were staged on seemingly short notice by group of aficionados running more on passion than professionalism. They were marketed as an oddity, with rings being put up outside malls to attract curious shoppers. The two events made more news for organisational goof ups – Krishan’s fight schedule had to be advanced after organisers feared the outdoor venue might be caught by rain showers.

Vijender’s promoters on the other hand believe they have things in place. Slick promos – with the theme ‘Return of the Singh’ are already playing on TV. Advertising rights and sponsorship deals for all parts of the stadium and Vijender’s clothing are being thrashed out. With certainly more people expected to tune in than the 20million who did for his professional debut, TV rights have been sold as well. The next few days will see the slow build up of fight week. The two prizefighters will do what it takes to generate even more buzz around the contest—press conferences, media workouts, a dance with a Bollywood A-lister on Wednesday, a TV appearance at a PKL game the day after and finally the weigh in and stare down a day before the fight — just the way the big boys do it around the world.

“Vijender is making his homecoming and It’s going to be like nothing India’has seen,” a beaming Francis Warren, CEO of Queensberry promotions had said at an event promoting the fight a few weeks ago in Delhi.

Brigadier Murali Raja, former president of the Indian amateur federation and current head of the IBC, a professional boxing organisation, which is the local co sanctioning body along with the WBO for Vijender’s title fight feels it could herald a new era for professional boxing in India. “I see Vijender doing for professional boxing in India what he did for amateur boxing after winning our first medal at the Olympics. Vijender will undoubtedly be the pathfinder,” he says.

Reality Checks in

Amidst all the breathless anticipation, it’s important to take a step back and look things through. While it is a significant step, Vijender’s homecoming and his title fight with Hope isn’t going to be a game changer – for either the sport or for his own year long career – just yet. Professional sport in India is increasingly packed with options each of which clamours for the same pool of sponsors and audiences. The stars ringside – Gautam Gambhir, Randeep Hooda, Ranijay (a veritable whose available) — aren’t expected to pay for their seats. Indeed with a week to go before the fight, tickets – despite being offered at a discount – have yet to be sold out. This perhaps explains why the fight, first expected to be held at the 20,000 seater IG stadium was eventually shifted to the smaller Thyagaraj stadium.

And while everyone wants to get onboard, how long the gravy train continues to chug along depends on how well one man, Vijender Singh fares in the ring. “Any sport needs winners for it to be popular,” says Raja simply. The man in the middle of it all, the one expected to be a pathfinder certainly knows so as do his promoters.

They’ve all done their part over the last year. Vijender, training under reknowned trainer Lee Beard in Manchester, has racked up an enviable 6-0 record with a hundred percent knockout ratio – a fine looking statistic. Naysayers may point out that the quality of his opponents wasn’t anywhere close to being of the highest calibre. At first glance it doesn’t seem a particularly harsh indictment. His first opponent Sonny Whiting was a scaffolder, his next Dean Gillen was a firefighter. Of his next four opponents, two – Matiuze Royer and Samet Hyuseinov had negative win loss records. Andrzej Soldra and Alexander Horvath had been more successful but a cursory look at their records indicated they had little power in their punches and not much ability to take them either.

But this wasn’t any devious attempt to shield Vijender from taking a career destroying loss early in his career. “There’s nothing he is doing which isn’t what another boxer will not be doing at this stage of his career,”says long time boxing correspondent Steve Lillis.

Lillis points out that each of Vijender’s opponents tested a different aspect of his game. “It makes no sense to throw a boxer who has just turned professional into the deep end. Vijender’s first six bouts were learning bouts. Whiting was an inexperienced boxer. Gillen had a 2-0 record when he fought Vijender. Hyuseinov didn’t have a great record but he was an opponent who had a bit of experience. Horvath didn’t have a lot of bouts but he had a few wins. Rouyer wasn’t a very strong boxer but he is someone who has the ability to take a punch and keep coming at you. In Soldra, Vijender was fighting someone who had a strong amateur background and also a decent professional record. All in all he’s faced a good range of fighters. They aren’t world beaters but they are getting better with every fight. His choice of opponents can’t be criticised,” says Lillis.

Rope in Hope

The bout with 34-year-old southpaw Hope, albeit for a title, can still be considered a learning bout. The Wales born Australian holds the WBC Asia Pacific middleweight title, the WBO Oriental middleweight title and formerly held the EBU European title at the same weight. With 30 bouts and a record of 23-7, he is easily Vijender’s most capable opponent. But with a low knockout ratio (just 2) Vijender’s match makers must believe Hope will challenge but not beat their fighter.

The expectation is that Hope will provide for Vijender some much needed ring time. The Indian admits as much himself. “I need more rounds. Its a good thing to be six wins but people ask me how many rounds I have fought and I know I still need experience,” he says. Lillis concurs. “Vijender is putting away his opponents right now quite easily and fans obviously like looking at knockouts but he needs to get some time in the ring. He needs to know what it’s like to fight 10 rounds of three minutes each with a minute’s break in between,” he says. A victory here will provide more tangible benefits as well. “Vijender will get a top15 ranking in the WBO world super middleweight ratings. That makes it easier for his promoters to set up higher profile bouts with better opponents in the future,” says Lillis.

And if all goes to Vijender’s plan on Saturday, his challenges will get tougher. “Once you are in the championship category (10 and 12 rounders), you wouldn’t get easy fights. Its only a small pool of fighters who can compete in championship rounds. His quality of opponents will improve. It won’t be as easy to knock someone out anymore and he will have to take a lot more punches than he has taken so far,” says Lillis.

And of course there won’t be an option of looking for an easier alternative. “There’s no going back now. Once I start boxing 10 and 12 rounds, I can’t decide I would rather fight weaker opponents in six round and four round contests,” says Vijender.

Indeed, stepping back is certainly not on his promoters minds. The Hope bout is seen as a harbinger of bigger things to come for the 30-year-old. “This bout will be a success but this is only the first round of Vijender’s career. We have a lot more rounds to go. But it is only going to be bigger things for Vijender now,” Tomar says. It was an optimism shared by Warren a month back as well. “I certainly believe that Vijender can fill up a cricket stadium at some point in his career,” he had said then.

For now though the task would simply be to sell out the last of the five thousand seats at the Thyagaraj Stadium.

His Pro-gress

A year ago when he made the decision to turn professional, Vijender was at a crossroads. Becoming a prizefighter meant that he would have to unlearn many of the tools and techniques he had picked up in his two-decades long amateur career. Over the course of his six professional contests however, the Indian has rebuilt his toolkit to become a more effective fighter. “It’s impressive how someone who became a professional boxer as late as he did in his career has adapted so quickly as he did,” says veteran boxing journalist Steve Lillis.

Energy— Unlike in the amateurs where boxers have to fight for just three rounds, professional fights are scheduled to last for up to 10 to 12 rounds. So while Vijender could fight at a relentless tempo in the amateurs, he had to learn to conserve his energy as a professional. The first thing to go was the typical bouncing foot movement. It has been replaced by a more measured advance that blocks off his opponent and allows him to lead him in the direction of his choice. This doesn’t mean that his defence is compromised. “The key to a good defence isn’t just that you keep moving. By staying balanced, Vijender is also able deliver his counter punches with a lot of power,”says his trainer Lee Beard.

Jab – the Jab is the one of the most crucial set up punches in professional boxing and Vijender’s left is certainly no exception. “His jab isn’t just a glove he extends in front of him. He delivers it like a backhand,” says Lillis. Vijender though had to be taught to use the punch effectively. “In the amateurs it wasn’t a scoring punch so I would not use it so frequently. But as a professional, you can use it to wear down your opponent,” he says. The Indian’s jab has plenty of deception. In his fight against Rouyer, he used a soft jab. The Frenchman kept his head down and walked repeatedly into Vijender right hook. In his final bout, his jab was delivered with more venom, hurting the Pole who eventually stopped advancing.

Power— Vijender’s big right hand is his biggest weapon. “When he first came into spar, I was surprised by the power in his right hand. I knew that if he ever landed it on an opponent in a contest, the fight would be over right there,” says trainer Beard. The Indian’s right too had to be worked on. “In the amateurs, you just have to get a touch from your gloves on your opponent and then get away. In the first couple of rounds of Vijender’s first fight against Whiting, he was doing that. We had to get him to get closer. He learned quickly as well. When he wasn’t punching at targets but through them, the contest got over quickly,” Beard says.

Weight – A key decision that had to be made by Vijender and his team was which weight should he fight at. For the bulk of his amateur career Vijender had fought at Olympic middleweight (75kg). The professional middleweight division is 2.5kg lighter (72.5kg). Vijender fought his first three bouts at that weight but Beard was concerned about the toll it was taking on his health. “He fell sick due to effects of cutting weight before his third bout. Vijender looked a lot better in sparring when he was 78-79kg. So the better decision was for him to move to supermiddleweight (76.5kg). He carries his power a lot better in that category and he is less likely to fall ill as well,” says Beard of Vijender who has fought at super middleweight ever since.

![]()